How is Behçet’s diagnosed?

There is no test for Behçet’s at the moment. It is diagnosed by specific patterns of symptoms and repeated outbreaks of them. Any other causes for these symptoms have to be ruled out first. The symptoms do not have to occur together but can have happened at any time.

Diagnostic Guidelines

There are levels of certainty for diagnosis (and additional knowledge since the original criteria):

- NHS England Diagnosis – Diagnosing Behçet’s Disease (as of 20 November 2019)

- The International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ICBD) (2013)

- Suspected or possible diagnosis (incomplete pattern of symptoms)

- Practical clinical diagnosis (generally agreed pattern but not so strict)

- International Study Group diagnostic guidelines (very strict for research purposes) (1990)

1. NHS England Diagnosis – Diagnosing Behçet’s disease (as of November 2019)

The main symptoms of Behçet’s disease include:

- genital and mouth ulcers

- red, painful eyes and blurred vision

- acne-like spots

- headaches

- painful, stiff and swollen joints

In severe cases, there’s also a risk of serious and potentially life-threatening problems, such as permanent vision loss and strokes. Most people with the condition experience episodes where their symptoms are severe (flare-ups or relapses), followed by periods where the symptoms disappear (remission).

There’s no definitive test that can be used to diagnose Behçet’s disease. Several tests may be necessary to check for signs of the condition, or to help rule out other causes, including:

- blood tests

- urine tests

- scans, such as X-rays, a computerised tomography (CT) scan or a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

- a skin biopsy

- a pathergy test – which involves pricking your skin with a needle to see if a particular red spot appears within the next day or two; people with Behçet’s disease often have particularly sensitive skin

Current guidelines state a diagnosis of Behçet’s disease can usually be confidently made if you’ve experienced at least three episodes of mouth ulcers over the past 12 months and you have at least two of the following symptoms:

- genital ulcers

- eye inflammation

- skin lesions (any unusual growths or abnormalities that develop on the skin)

- pathergy (hypersensitive skin)

Other potential causes also need to be ruled out before the diagnosis is made.

2. The International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ICBD) (2013)

An International Team for the Revision of the International Criteria for BD (from 27 countries (though not the UK)) submitted data from 2556 clinically diagnosed BD patients and 1163 controls with BD-mimicking diseases or presenting at least one major BD sign. The new proposed criteria derived from multinational data exhibits much improved sensitivity over the [original] ISG criteria while maintaining reasonable specificity. It is proposed that the ICBD criteria to be adopted both as a guide for diagnosis and classification of BD.

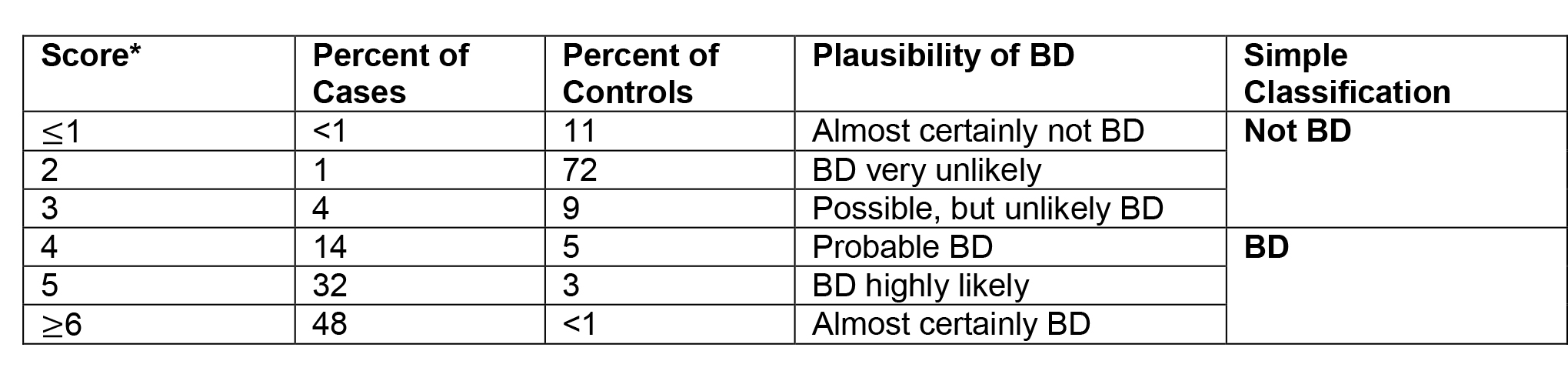

The final proposed criteria included oral aphthosis, genital aphthosis, ocular lesions (anterior uveitis, posterior uveitis, or retinal vasculitis), neurological manifestations, skin lesions (pseudofolliculitis, skin aphthosis, erythema nodosum) and vascular manifestations (arterial thrombosis, large vein thrombosis, phlebitis or superficial phlebitis). Oral aphthosis, genital aphthosis and ocular lesions were each given 2 points, whereas 1 point was assigned to each of skin lesions, vascular manifestations and neurological manifestations. A patient scoring 4 points or above was classified as having BD (Table 5).

Table 5 – International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease – point score system: scoring ≥4 indicates Behçet’s diagnosis.

Society note: While the criteria are useful in allowing additional symptoms to be considered – as they note, “…exhibits much-improved sensitivity over the [original]…” merely relying on Oral and Genital ulcers, thus scoring ≥4, is too simplistic and can lead to over-diagnosis. In the UK population where Behçets Disease is rare, the use of the 2014 criteria results in a loss of specificity compared to the ISG (1990) criteria. The (multi-disciplinary) National Centre of Excellence supports this view.

*Pathergy test is optional and the primary scoring system does not include pathergy testing. However, where pathergy testing is conducted one extra point may be assigned for a positive result.

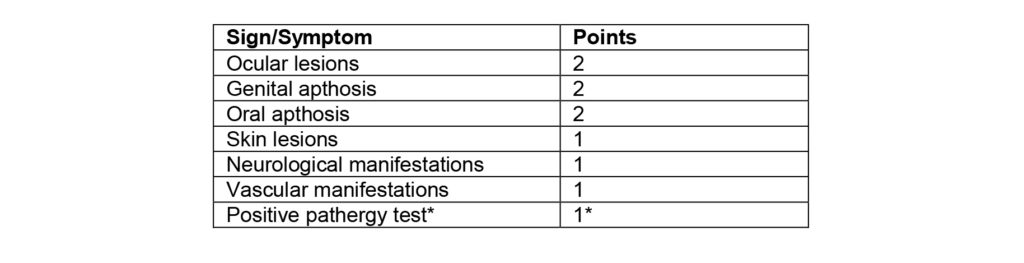

The distribution of scores in cases and controls in both validation and training data sets along with a proposed plausibility scale of BD diagnosis is presented in Table 6.

Table 6

The PDF of the ICBD document can be viewed here

3. ‘Suspected’ or ‘possible’ diagnosis

This is usually given when someone does not have mouth ulcers or has mouth ulcers but does not have 1 of the 4 ‘hallmark’ symptoms but has other symptoms and signs of inflammation and other causes for these have been ruled out.

Symptom proportions for members of the Behçet’s UK (then Behçet’s Syndrome Society) in the UK (survey dated 1994)

| Symptom | % of people with symptom |

| Mouth ulcers | 100 |

| Arthritis/arthralgia | 93 |

| Genital ulcers | 89 |

| Skin lesions | 86 |

| Eye inflammation | 68 |

| Tissue reactivity (pathergy) | 32 |

| Thrombophlebitis | 32 |

| Neurological problems | 31 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 28 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 22 |

(Other symptoms were not measured)

4. Practical clinical guidelines for patients not included in research cohorts

Must have:

- mouth ulcers

Along with 1 out of the 4 ‘hallmark’ symptoms above

Along with 2 of the following symptoms:

- arthritis/arthralgia

- nervous system symptoms

- stomach and/or bowel inflammation

- deep vein thrombosis

- superficial thrombophlebitis

- cardiovascular problems

- inflammatory problems in chest and lungs

- problems with hearing and/or balance

- extreme exhaustion

- changes of personality, psychoses

- any other member of the family with a diagnosis of Behçet’s

5. International Study Group strict research level guidelines for diagnosis (1990)

Must have:

- mouth ulcers (any shape, size or number at least 3 times in any 12 months)

Along with 2 out of the next 4 ‘hallmark’ symptoms:

- genital ulcers (including anal ulcers and spots in the genital region and swollen testicles or epididymitis in men)

- skin lesions (papulo-pustules, folliculitis, erythema nodosum, acne in post-adolescents not on corticosteroids)

- eye inflammation (iritis, uveitis, retinal vasculitis, cells in the vitreous)

- pathergy reaction (papule >2 mm diameter, 24-48 hrs or more after needle-prick)

Criteria for diagnosis of Behcet’s disease, ISG (1990) The Lancet, 05 May 1990